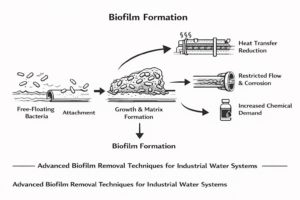

Microbial growth is one of the most common and costly challenges in water systems, and it often starts quietly. When a small microbial population attaches to surfaces and environmental factors such as temperature, stagnation, oxygen levels, and nutrient availability align, biofilm forms and control becomes more difficult and more expensive. This pattern can develop in cooling towers, boiler and condensate systems, process water circuits, and building plumbing.

The impacts go well beyond water quality. Microbial activity can reduce heat transfer, increase corrosion potential, and drive fouling in piping, strainers, and heat exchangers. In aerosol-generating equipment and building water systems, uncontrolled biological activity can also increase the risk of infectious agents spreading through droplets or mist. The good news is that prevention is achievable through a consistent program built on monitoring, deposit control, and properly applied biocide strategies that help water treatment professionals avoid optimal growth conditions and stop rapid growth before it takes hold.

What Microbial Growth Actually Means: From a Single Cell to Biofilm

According to Linda Bruslind’s journal from Oregon State University, Microbial growth in water systems is best understood as a combination of cell growth and surface attachment, not just “bacteria in the water.” In microbiology, microbial growth refers to an increase in cell number as organisms reproduce over time.

Microbes exist both as free-floating cells in the bulk water and as attached communities on surfaces such as piping, heat exchanger tubes, fill media, and tank walls. Once attached, many organisms form biofilm, a protective layer that concentrates nutrients and shields microbes from treatment. Even when water looks clean, biofilm can hold a dense microbial population that continuously releases cells back into circulation, which is why controlling attachment and deposits is as important as controlling the bulk water.

The Microbial Growth Curve in Water Systems (The “Why It Takes Off”)

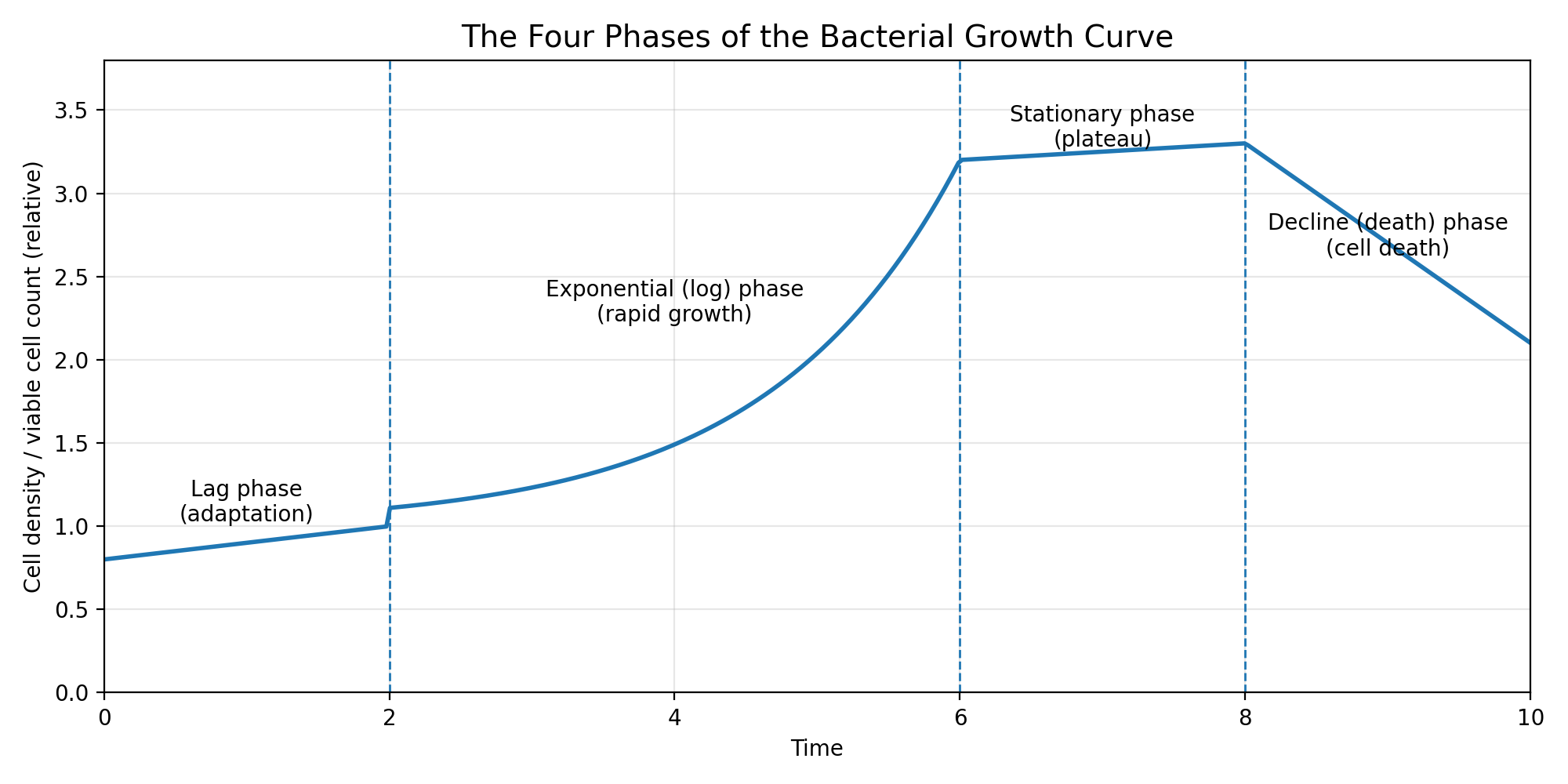

To prevent biological fouling effectively, it helps to understand a foundational concept from microbiology: the microbial growth curve, sometimes called the bacterial growth curve. In the laboratory, microbiologists track how a bacterial population changes over time in a controlled environment. In the field, water systems are not sterile, but the same growth curve principles still apply because microorganisms respond predictably to changing conditions.

A typical bacterial growth cycle is described in four distinct phases. These distinct phases explain why microbial control can seem stable for weeks, then suddenly shift into rapid growth.

The Four Phases of the Bacterial Growth Curve

1) Lag phase

In the lag phase, cells adapt to new environmental conditions. They are metabolically active, producing necessary enzymes, repairing damage, and preparing for cell division. The cell number may change very little at this stage, but the population is getting ready for growth.

2) Exponential phase (log phase)

During the exponential phase, also called the log phase, the bacterial population increases exponentially. Cells divide at a near-constant rate, and each parent cell produces two daughter cells that are genetically identical. Because the doubling time (or generation time) can be short, the number of cells rises rapidly and cell density can spike. This phase reflects high bacterial growth rates and may approach the system’s maximum specific growth rate, especially under optimal conditions.

3) Stationary phase

In the stationary phase, growth slows as nutrients are depleted, oxygen levels change, and waste products accumulate. The growth rate stabilizes because new cells are produced at roughly the same rate as cell death occurs. Biofilm often strengthens here, making control more difficult.

4) Decline phase (death phase)

In the decline phase, also called the death phase, conditions no longer support survival. Cell death exceeds growth, leading to more dead cells and fewer viable cells. However, decline does not guarantee elimination because biofilm can protect survivors and enable regrowth when conditions improve.

Where Microbial Growth Happens: Common Water System Hot Spots

Microbial issues rarely appear uniformly across an entire system. Instead, microbial populations concentrate in specific areas where environmental factors support attachment, protection, and steady access to nutrients. These hot spots are especially common where flow is inconsistent, deposits accumulate, or operating conditions shift throughout the day. Understanding where growth begins helps water treatment professionals prioritize inspections, sampling points, and preventive maintenance.

High-risk areas in common water systems

Cooling towers and open-recirculating systems

Cooling towers provide oxygen-rich water, warm temperatures, and continuous introduction of airborne debris. These conditions support high microbial activity and rapid biofilm formation. Areas with high surface area, such as fill media, basins, and drift eliminators, can also become reservoirs for microbial growth. If solids are not controlled, the buildup can increase cell density in protected zones, allowing populations to expand between biocide applications.

Closed loops and process water circuits

Even in closed systems, microbial growth can occur when oxygen is introduced through leaks, makeup water, or maintenance events. Biofilm can form in low-flow branches, around strainers, or in dead legs where water sits for long periods. Over time, microbial waste products can accumulate locally, and deposits can create sheltered microenvironments where organisms persist, even under adverse conditions.

Boiler systems and associated feedwater equipment

Boilers themselves typically operate at temperatures that inhibit most bacteria, but microbial growth can occur in cooler pre-boiler sections such as storage tanks, condensate return piping, or feedwater systems. If oxygen levels and nutrients are present, these regions can support microbial populations that contribute to under-deposit corrosion and fouling upstream of the boiler.

Building plumbing and potable water systems

Plumbing networks often contain conditions that encourage growth, including warm zones, stagnation, and inconsistent disinfectant residuals. Low temperatures help slow microbial activity, but they do not eliminate it. Some organisms can persist for long periods, especially in biofilm. Distal outlets, mixing valves, storage tanks, and infrequently used fixtures are common problem areas.

Any place where water slows down or deposits build up

Across all system types, the most consistent pattern is this: microbial growth increases where solids and nutrients collect and where disinfectant contact is reduced. These are the areas where microbial communities can establish, recover quickly, and spread back into the bulk water during flow changes.

Root Causes: Why Microbial Growth Gets Out of Control

Microbial growth in water systems is rarely triggered by one failure. More often, several changes combine to create optimal growth conditions, allowing microbial populations to shift from slow activity into active growth. When environmental factors align, even a stable system can experience rapid growth.

- Temperature and time: Warm water accelerates cell metabolism, while stagnation and long periods of low flow allow disinfectant residuals to decay and nutrients to concentrate. Cold temperatures and low temperatures can slow activity, but they do not create a sterile medium. Many organisms persist in biofilm during sub optimal conditions and rebound when conditions improve.

- Nutrients and chemistry: Water systems can unintentionally behave like culture media when essential nutrients, organic matter, or process contaminants are introduced. The chemical composition of the water, including pH and solids, influences microbial activity and disinfectant performance.

- Deposits and corrosion products: Scale and sediment create protected niches where bacteria attach and form biofilm. The cell wall and cell membrane help bacteria survive stress, especially inside mature biofilm where biocides have less access.

- Inconsistent biocide exposure: Intermittent treatment can suppress free-floating organisms but leave reservoirs that repopulate quickly, pushing the system back toward maximum growth rate.

Proven Prevention Strategies: A Program Approach

Microbial control is most successful when it is treated as an ongoing program rather than an occasional response. In practical terms, prevention means two things. First, avoid creating optimal growth conditions. Second, verify performance using meaningful monitoring so changes are detected early, before microbial populations reach rapid growth.

A proven program approach focuses on controlling conditions that support microbial growth and maintaining consistent treatment over time.

Control the Conditions Microbes Need to Thrive

Microbial growth is driven by environmental factors. When those factors are managed, microbes struggle to move beyond the lag phase and cannot sustain exponential growth. Prevention is not about eliminating every organism. It is about keeping the system in adverse conditions that prevent population expansion and biofilm persistence.

Key control areas include:

1) Reduce stagnation and water age

- Remove or minimize dead legs, low-flow branches, and rarely used piping where practical.

- Establish flushing routines for low-use outlets and seasonal systems.

- Keep circulation consistent, especially in warm zones.

- Verify flow patterns during operating changes or shutdowns.

Why it matters: long periods of stagnation reduce disinfectant effectiveness and concentrate nutrients. When flow returns, the system can reseed with organisms from protected pockets.

2) Control temperature where possible

- In building systems, keep hot water hot and cold water cold, and avoid extended “lukewarm zones.”

- In industrial systems, recognize that warm operating temperatures can push microbes into active growth, especially when disinfectant contact is inconsistent.

Why it matters: warmer temperatures often accelerate cell metabolism, shorten doubling time, and increase growth rate. Temperature control alone is not a biocide program, but it is a strong prevention lever.

3) Control deposits, scale, and organic loading

- Optimize filtration and solids control where applicable.

- Maintain deposit control chemistry and dispersant strategy.

- Inspect and clean high-risk areas on a schedule, including basins, strainers, and low-flow zones.

- Treat fouling as both a mechanical and microbiological issue.

Why it matters: deposits shelter organisms, increase cell density locally, and reduce biocide penetration. Removing the habitat reduces microbial populations more effectively than increasing dose alone.

4) Manage oxygen levels and system boundaries

- Understand where oxygen enters closed systems through leaks, maintenance, or makeup water.

- Minimize air intrusion, and control corrosion and solids that follow oxygen ingress.

Why it matters: oxygen levels influence which microbial species dominate and how quickly biofilm can establish.

Biocide Strategy: Oxidizers, Non-Oxidizers, and Program Design

Biocide programs are strongest when they are designed around how microbial populations actually behave. A single method rarely covers every organism and every growth phase. Program design should consider microbial species diversity, biofilm resistance, system hydraulics, and seasonal variation.

A practical approach for many systems includes:

- Routine oxidizing biocide control to suppress planktonic organisms and reduce the overall bacterial population.

- Strategic non-oxidizing biocide applications to broaden the kill spectrum, disrupt biofilm communities, and address organisms that tolerate oxidizers.

- Consistent dosing and contact time to avoid intermittent exposure that allows recovery and adaptation.

Important concept: when treatment is inconsistent, organisms move back into active growth. Bacterial growth rates can increase quickly when conditions shift, especially when deposits and nutrients are present. Prevention is easier when biocide exposure is steady and predictable.

Deposit Control and Cleaning: Don’t Treat Through Biofilm

Biofilm and deposits create physical protection for microbes. As biofilm matures, it can trap dead cells, waste products, and nutrients, creating a stable environment for regrowth.

To reduce biofilm pressure:

- Use dispersants and deposit control chemistry aligned to the system.

- Schedule physical cleaning where it makes sense, particularly in towers and basins.

- Treat cleaning as part of prevention, not only as remediation.

The most effective programs combine chemistry and housekeeping. Removing the habitat lowers microbial pressure and reduces chemical demand.

Monitoring and Verification: Measure What Matters

Prevention is only reliable when it is verified. Monitoring should confirm whether control measures are keeping microbial levels stable and preventing growth curve acceleration.

Common monitoring methods include:

- Colony forming units (CFU) estimates using dip slides or culture-based methods, which reflect viable cells.

- Tracking trends in cell density, not just one-off results.

- Monitoring supporting parameters such as temperature, pH, oxidizer residual, and system cleanliness indicators.

Trend matters more than any single data point. A steady increase in viable cells or CFU often signals that microbial populations are shifting into active growth, even if the water still looks clean.

Batch vs Continuous Control: Why Steady Programs Work Better Than Occasional “Shocks”

Many water systems behave like microbiology experiments. When conditions suddenly improve, microbes respond quickly. A one-time “shock” approach is similar to batch culture, where organisms experience a short period of strong control followed by time to rebound. After a shock, surviving organisms can repopulate, especially if deposits remain and the system continues providing culture media conditions.

A steadier approach resembles continuous culture, where control measures are maintained at a consistent level. In continuous culture, adding fresh medium is balanced by removing waste products and maintaining stable conditions. While real systems are not a sterile medium, the principle still applies. Consistency helps keep microbial activity low, reduces swings in cell density, and limits opportunities for organisms to reach maximum specific growth rate.

Batch vs Continuous Control in Real Water Systems

| Program approach | Microbiology analogy | What it looks like in the field | Common outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shock-based control | Batch culture | Infrequent high-dose treatments with gaps between applications; deposits remain; inconsistent control | Microbes recover between events, higher chance of rebound and biofilm persistence |

| Steady, program-based control | Continuous culture | Consistent dosing strategy; predictable residuals; regular deposit control; routine monitoring | Lower biological swings, improved stability, reduced risk of rapid regrowth |

Sudden operational changes can also trigger diauxic growth, where microbes shift metabolism when nutrient sources change. This is another reason steady programs typically outperform reactive ones.

ETI’s Support for Microbial Control Programs

Effective microbial control requires more than choosing a biocide. It requires the right chemistry, the right monitoring, and the right technical guidance to keep microbial populations from shifting into active growth. ETI supports water treatment professionals by providing a comprehensive portfolio of microbiological control solutions and the technical expertise needed to apply them correctly.

ETI offers 35+ microbiocide chemistries, including oxidizing and non-oxidizing biocides, available under a manufacturer’s label or private label. This flexibility helps partners tailor programs to different bacterial species, system conditions, and risk profiles, while maintaining consistent control of viable cells in the bulk water and reducing biofilm pressure. ETI also assists partners with US-EPA supplemental registrations when needed for product distribution and labeling.

Beyond chemistry, ETI’s technical team brings 95+ years of combined experience, supporting troubleshooting, field problem-solving, and program optimization. ETI also provides specialized monitoring options, including the Glutatect WT Test Kit for measuring glutaraldehyde residuals and the HMB X System for biofilm activity monitoring, along with laboratory and jar testing support that can help partners validate program performance.

Contact ETI for Microbial Control Support

If you are looking to strengthen microbial control across cooling towers, boiler systems, wastewater applications, or specialized water systems, ETI is here to support your program. ETI works exclusively with independent water treatment service companies and OEM partners, providing the chemistry, technical resources, and responsive assistance needed to help you deliver consistent results for your customers.

To discuss biocide program design, monitoring options, custom formulations, or regulatory support, contact ETI’s technical team today.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is meant by microbial growth?

Microbial growth refers to an increase in the number of microorganisms over time as cells reproduce, which results in a higher cell number in a system. In many cases, this increase happens through cell division such as binary fission, where one parent cell produces two daughter cells. In water systems, microbial growth often becomes a concern when microbes attach to surfaces and form biofilm, allowing microbial populations to persist and spread. This is why monitoring viable cells and trending results such as colony forming units can help identify growth before it becomes visible.

Is microbial growth the same as mold?

No. Mold is a type of fungus, while microbial growth is a broader term that includes bacteria, fungi, algae, and other microbial species. In water systems, bacterial cells and biofilm are often the primary drivers of fouling and corrosion, although fungi can also contribute in certain environments. Mold is typically associated with damp surfaces and air exposure rather than circulating industrial water loops. Both can be controlled by managing environmental conditions, cleanliness, and treatment consistency.

What are the 4 stages of microbial growth?

The microbial growth curve is commonly described in four phases: lag phase, exponential phase (log phase), stationary phase, and decline phase (death phase). In the lag phase, cells adapt and prepare for reproduction. During exponential growth, the bacterial population increases exponentially as cell division occurs at a rapid, near-constant rate. In stationary and decline phases, nutrient limitations, waste products, and adverse conditions slow growth and increase cell death.

Is microbial good or bad?

Microbial activity can be both beneficial and harmful, depending on the application and level of control. In wastewater treatment, managed microbial populations can be essential for breaking down organics and supporting bioaugmentation processes. In cooling towers, boilers, process systems, and building plumbing, uncontrolled microbial growth can lead to biofilm, corrosion, fouling, and increased operating cost. The goal in most water systems is not sterility, but stable conditions that prevent rapid growth and reduce risk.